At VRR, we go all out to build ULDs that help customers meet tomorrow’s challenges. So, thinking about how we’ll be transporting air cargo in years to come is part and parcel of what we do. It helps us to innovate in collaboration with our partners. This article is the first in a series that will be looking at all kinds of future mobility.

When you talk about future aircraft, there are two topics you can’t avoid: efficiency and sustainability. Airlines are starting to replace massive, high-capacity planes with smaller, cheaper and faster jets. They’re easier to fill, and they’re much more flexible. What’s more, they emit fewer CO2 emissions per passenger or kilogram of cargo, helping to lessen the environmental impacts of air transportation.

For airlines and carriers looking to reduce their carbon footprint as well as their operational costs (which is probably all of them), the next generation of jetliners can’t come soon enough. They’ll make low-demand routes more profitable, allow more non-stop routes to be flown, and contribute to sustainability targets.

It's an interesting development for those involved in transporting cargo by air. On the one hand, more efficient aircraft and more direct routes will help them to increase scheduling options, lower operating costs and cut carbon emissions per consignment. On the other hand, could the shift to smaller planes for long-haul flights force them to rethink the mix and the design of containers they currently have in their ULD fleets?

While all this unfolds, at VRR we’re also keeping an eye on planes that are not yet roaming the skies (at least commercially). Staying informed of new aircraft designs helps us to anticipate customer requirements and to create air cargo containers that are ready for the future.

A snapshot of aircraft of the future

The almost-here planes

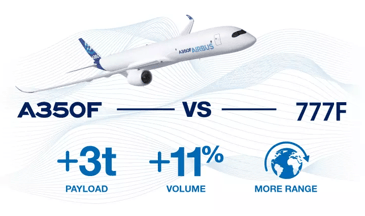

When it comes to dedicated freighter planes, the industry is anticipating the arrival of not one but two in the near future. The A350F (due 2025) and the 777-8F (due 2027) will soon be giving air cargo carriers latest-generation efficiency in the wide-bodied category.

Both plane makers are touting huge improvements in fuel efficiency, emissions and operating costs compared to the current generation of heavy freighters. The A350F is stated to have a 20% lower fuel burn and 11% more volume than the 777F, while the 777-8F is being marketed as the most efficient and versatile medium widebody freighter there is.

Airbus is touting the 350F as the future of the large widebody freighter market

Airbus is touting the 350F as the future of the large widebody freighter market

Airbus and Boeing are also set to deliver new passenger jets in 2024 and 2025 respectively. The single-aisle A321XLR is said to offer a 30% improvement in fuel consumption per seat compared with previous generation aircraft, thanks to its more aerodynamic winglets and improved engine performance.

Meanwhile, the 777x is being promoted as the world’s most efficient twin-aisle aircraft. Design and technology improvements such as lighter and more aerodynamic wings promise a 10% reduction in fuel burn and CO2 emissions, plus a 10% increase in operating economics.

The far-into-the-future planes

While the planes due to be delivered in the next few years promise to be much more efficient, their designs don’t differ radically from those already in the air. The same can’t be said for the following bunch of aircraft. Their concepts are truly futuristic.

-

Developing alternative propulsion systems

The ZEROe concepts by Airbus all use hydrogen propulsion. The three distinctive passenger jet planes are powered by hydrogen combustion through modified gas turbine engines and use liquid hydrogen as fuel for combustion with oxygen. Could this be the world's first zero-emission aircraft by 2035, as the manufacturer pledges? Perhaps, but only if the hydrogen that it uses doesn’t come from methane (a fossil fuel), as is the case with most hydrogen supplies today.For short-range flights, how about battery power? Alice, the world’s first all-electric passenger jet, took her maiden flight in September 2022. With a maximum useful load of up to 2,600 pounds (around nine passengers) and a range of 250 miles, the transition to much larger electric jetliners is still only an aspiration. But makers Startup Eviation are convinced that short- and medium-range planes could soon be making the switch to batteries without too much pain.

Electric planes are extremely quiet, making them ideal for

Electric planes are extremely quiet, making them ideal for

locations with noise ordinances.

-

Rethinking conventional wing design

Aerodynamics is another way to make planes more efficient and maybe even greener. Airbus is looking at a blended wing design. The MAVERIC, which is one of the three ZEROe concepts, uses the whole airframe to provide lift, making it lighter and smaller yet still able (potentially) to carry the same payload.Meanwhile, Boeing has been working with NASA for almost 15 years on a concept called the Transonic Truss-Braced Wing (TTBW). It involves a longer, thinner wing that is supported from beneath the fuselage. Boeing says the new design would need 9% less fuel than a conventional design, while NASA is hoping to cut fuel consumption and emissions by up to 30% if the TTBW can be coupled with improvements in propulsion, materials and architecture.

The big boys of aircraft manufacturing are not the only ones experimenting with revolutionary wing design. At Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, researchers are plugging away at a design known as the "Flying-V". They believe this visionary concept for long-haul passenger aircraft would be up to 20% more efficient than a modern plane like the Airbus A350.

-

Ditching pilots for drones

From passenger planes to unmanned air vehicles. Yes, there are several companies developing all sizes of drones, from single package drones to medium- and large-sized drones that can carry up to several tons. Take California-based Natilus. It’s developing huge autonomous cargo drones that will apparently hold up to 60% more cargo than same-sized standard aircraft thanks to their diamond-shaped freight areas. Too far-fetched? Pre-orders for more than 440 of these aircraft have already been placed.

What do these new planes mean for air cargo transportation?

The concepts above are just a snapshot of the work being done to develop aircraft of the future, yet they indicate the pressure on aircraft manufacturers to think radical, largely as a result of sustainability concerns. But as fantastic as the claims for aircraft efficiency are, what are the practical implications for handling, loading and carrying cargo in the future? In particular, the impact these designs will have on ULDs. Here are our thoughts:

-

Existing infrastructure

Aircraft of the future must be able to use existing infrastructure, from airport runways and parking slots to humble pallets and containers. Designers need to consider loading and unloading processes at the concept stage. There’s no point shaving two hours off a flight if cargo handling slows down by two hours because high loaders cannot access the hold easily. -

Modified cargo bays

In a similar vein, cargo bays can be an afterthought for aircraft designers. As a result, they often need modification to make them compatible with new aircraft. Likewise, those who plan and design cargo facilities must be prepared to accommodate next-generation cargo aircraft that may well have longer wings, a higher tail or a non-conventional fuselage. -

ULD compatibility

There’s a lot of standardisation among ULDs, which means current aircraft are compatible with several types of containers. New aircraft must allow existing ULDs to fit optimally in the cargo hold. Slight modifications to a ULD’s design might benefit an airline’s operations, but the interchangeability of ULDs between different types of aircraft must be maintained. -

ULD construction

Despite the continuing need for standardisation, ULD manufacturers should reconcile themselves with the smaller, lighter aspects of next-generation planes. These aircraft will require less heavy, more compact cargo containers that nonetheless retain capacity and functionality. Incorporating such elements into future designs will be a technical but not (we think) impossible challenge.

Wrapping it all up

The aircraft of the future are promising great things in terms of efficiency and sustainability, including fewer emissions per kilo of cargo transported. However, those efficiency gains will be diminished if designers do not consider practical issues such as loading processes and optimum use of space in cargo holds.

Having said that, new types of planes open up all kinds of possibilities for new types of ULDs, such as inflatable or diamond-shaped containers. If early-stage collaboration between aircraft manufacturers, ULD manufacturers and cargo facility designers takes place, the future of air cargo transportation should be a happy and productive one.